When people find out I work from home and I'm my own boss, their almost invariable reaction is: “I’d never get anything done.”

My response is: “Sure you would—if you wanted to pay your bills.”

The questioner smiles and nods but then says something along the lines of: “But I’m not that disciplined. I’d sleep in then sit around in pajamas watching TV all day.”

Other questions include: “How do manage your time? How do you stay focused? What does a typical day look like for you? How do you stay sane?” And most popular of all: “As a wife and mother, writer/illustrator/editor, how on earth do you get it all done?” I’m amazed at just how often I receive these questions and with how much longing they’re asked. Many people dream of working from home, or of being a full-time writer, but just have no idea how to make it work for them time, discipline, and sanity-wise.

Whether you’re a freelancer with your own business, a full-time writer or illustrator, or a creative person trying to get your project completed beyond the 9 to 5, staying in focus, on target, and in balance can be very tough, especially when the demands of home life including family, chores, and various distractions are all so close at hand.

So, I’m going to answer these questions and provide some tools in the hope that showing what works for me will help you develop systems, balance, and success in your freelance or creative life. (While these tools work for the freelancer, many also translate well to the writer or illustrator trying to make progress with limited time—I know all too well what that’s like.)

Starting your workday right—setting yourself up for success: First of all, I strongly recommend that you do NOT sleep in or sit around in pajamas all day. Treat your freelance or work-from-home job like any other and rise and prepare in time to get to work on time. (What that time is for you you’ll need to work out based on your natural rhythms and what else goes on in your day. I will talk about that in a moment.)

While I don’t go to work in heels and a pencil skirt, I do walk the dog, bathe, dress, groom, eat a healthy breakfast, and arrive at my desk by 7:30 each day. This routine and attention to self-care and healthy living just set up the right mental attitude, and you’ll feel better about yourself as the day progresses, I guarantee.

Systems: One of the great things about working freelance is the freedom and malleability of one’s day (though many freelancers I know work even longer hours than those who “go” to work). But just as systems are important to a multi-person business or corporation, they are equally important to the freelancer who wants to get anything done and grow a successful business—or get that novel written. I truly believe that for the freelancer, systems are the key to living a productive, healthy, balanced, and successful freelance life.

So where do you even start? I’d begin by mapping a typical day.

Your day, like mine, can probably be divided into distinct sections. Here’s how I divide mine based on when I rise, family needs, other stuff I need to get done, etc. in order to work out my optimum periods for working. (I define “free time” in this case as any time that isn’t taken by the needs of others.)

- Pre 6:30: free

- 6:30-7:30: family morning routine

- 7:30-1:30: free

- 1:45-5: free-ish—my daughter is home so there are frequent distractions

- 5-9: family phone calls, dinner prep, family time, etc.

- 9-bedtime: free

As you see, I have four distinct periods of “free time,” and Prime Time—my optimum, distraction-free work period—is between 7:30 and 1:30 because I’m an early to bed, early to rise sort of person. Therefore, I schedule all matters that require a “distraction-free” environment within those hours. During Prime Time, my phone is off, I use social media blockers (see below), and I accomplish the bulk of my work.

Take this opportunity to map out the distinct sections of your day and define your Prime Time(s). Try to make sure you have a 7 to 8 hour period (or two blocks half that length), no matter what time of day in which they fall. (Are you an owl, rather than a chicken? I have some freelancer friends who start late and work until 1 or 2 AM, and you may find that is perfect for you, too.)

Mapping your day into distinct time periods for specific purposes will help you stay in balance. It sounds simple, doesn’t it? But when you work from home, your environment is never truly distraction-free. There is always something to be done: chores, errands, phone calls, and so many other distractions (such as family and social media) and all with no boss watching over you, cracking the whip.

So now we know when we can work, how do we stay both on target and in focus?

The List: The first task on my agenda each morning (and the last before I finish for the day) is making The List. Everything I need to achieve that day goes on The List. EVERYTHING (except things I obviously do each day such as bathing and cooking dinner). A typical day's list might include:

- Walk Phoebe (my dog)

- Reply... (and I individually list each email I have to respond to. I add to this the moment an email arrives.)

- Workout

- 10,000 steps

- Finish and return Client Project A

- Call my mum

- Reach point Y on Client Project B

- Pay bill Z

- Post office and bank

- Clothes washing

- Write blog post

- Make progress C on My Creative Project X

Etc.

Once I have a clear idea of what I need to achieve today, I can prioritize and start to chip away at it. The List, as well as providing a clear outline, helps provide accountability—it’s much harder to “forget” or ignore something that’s written on a to-do list in your clear line of sight.

The other benefits of using a list:

I start my list the night before, and I write it in a lined journal (one journal lasts the whole year), but explore what method works for you. The moment I realize I cannot complete a task today, I begin my list for tomorrow.

The list also gives me a feeling of freedom. I know what I have to get done, but no one tells me what order to do it in. It almost becomes like a puzzle, a game of logic and skill I play with myself—how to fit it all in.

Email: It is my policy to answer email rapidly. Partly, that’s the nature of my competitive job—you snooze, you lose that potential client—but it carries through to all other emails as well. First thing each day, I check my inbox, delete what I can, file to specific folders anything I need to keep, and add those that need to be answered to my daily list. Then I answer as many of those emails as I can. An empty inbox is a happy inbox.

Keeping up with the clerical work: I don’t have a secretary or an accounts department. The moment I receive payment from a client, no matter what I'm doing, I confirm receipt with the client, update my income sheets, and direct the money to where it needs to go (commissions, savings, working account). Don’t wait until tomorrow. Do it now. It’s too easy for such things to snowball otherwise.

Phone calls: If I have phone calls with clients, I schedule them within a two hour period in the morning or after Prime Time. Otherwise, I don’t answer my phone, which the nature of my business allows. The goal is to maximize uninterrupted, low-distraction time.

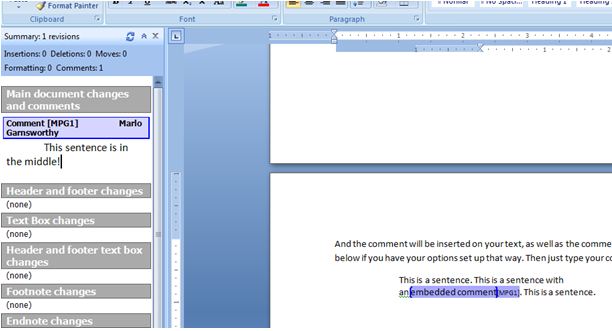

Staying focused during Prime Time: I use a Pomodoro style timer on my Internet browser called Strict Workflow, though a simple Internet search will provide many other free plugins for your browser. The Pomodoro method dictates 25 minutes of work followed by a 5 minute break.

It’s important to get up and move around during that 5 minutes to give both body and mind a break. Use this time for boiling the kettle, transferring the washing to the dryer, unpacking the dishwasher, talking to your pet, jumping jacks etc.—anything that moves your body and frees your mind a little. You'll be amazed by how many pesky chores you can knock off your list in this time.

Social media: In my industry, social media is very important for network building and info-sharing. It’s also great for eliminating the isolation that can come from working alone. I have a large number of friends in the publishing industry who also work from home, and we enjoy our visits to the “virtual water cooler” throughout the day. But social media can quickly become a terrible time-suck. There are plug-ins like I just mentioned that block the social media and other websites for the amount of time you specify—which is marvelous.

Deadlines: Nothing much to say here except, “Make them and keep them.” Your clients or your creative project will thank you, and you’ll be much happier, too.

Distraction Time: Since my child is home by 2 PM, the energy changes in the afternoon, so I segue to activities I can tackle successfully in short bursts, those that don’t suffer from interruptions. I get a lot of the household chores done during this time, phone calls, more emails, and I also use this time to think about the projects I’m working on—I often have bursts of inspiration about how to solve peoples' narrative issues at this time, for example, so I am frequently back at my desk during this afternoon period, feverishly jotting down notes on how John Doe's narrative arc could be strengthened by this or that or editing ever more pages. I also work on my own creative projects then. It is a much less structured part of my day, but equally productive. What activities can you schedule for your own Distraction Time in order to feel productive and successful? Dividing your workday into Prime Time and Distraction Time will create a much less stressful workday.

Staying motivated: It’s not always easy to stay motivated in any job, but here’s my trick for staying fresh: I like to have several projects underway at any given time. This allows me to segue to something else before I get stale and keeps the deadlines turning over on time without real stress. It also allows my subconscious to solve some of the issues in other projects, without having to force it. Oh, and walking the dog—there’s nothing like a burst of fresh air and a tail wagging in front of you to keep you fresh and happy.

Staying Healthy: Health professionals recommend that we each take 10,000 steps a day in order to stay healthy. For anyone with a sedentary job, this can be quite challenging to achieve, but for the freelancer it is totally doable if you plan accordingly and then take action. There are many pedometer apps to choose from that will keep track of your steps.

If the weather isn’t cooperating and you’re really pressed for time, your Pomodoro timer is your friend. In your 5 minute break, you can add 1000, 2000, or even more steps by walking around the house, walking up and down the steps, running in place, etc. If you’re into using time as effectively as possible in order to maximize your creative downtime, why not use this 5 minute break to do some dishes, put on another load of washing, move your body, and give your mind a break? You’ll be amazed by how many steps you add to your daily regimen and how much you get done. And if you’ve already whittled down the number of chores by the time you get to the end of Prime Time, you’ll find you have more time for your own creative pursuits—or for getting some “real” exercise such as going for a brisk walk or to the gym, etc.

Also, while I’m on the subject of staying healthy as a freelancer, I recommend making ahead a pot of healthy, protein-packed soup or casserole that you only need to heat and eat, and do eat at whatever you specify as lunchtime and snack time each day. It will help you avoid the urge to snack on less healthy items—but it’s even better if you just don’t keep those in your “office.”

Downtime: And in the evening? Any freelancer who wants to be successful has to be flexible enough to answer the occasional evening email; however, family time and downtime are vital. What I do do is start The List for the next day, but otherwise I try to avoid the office.

But for many of us who are trying to get a book written, our “downtime” may be the only time we have to write or to make progress on that project close to our heart.

Use little bits of downtime wisely. As you do the chores, keep a notebook or memo recorder at hand; inspiration often strikes at such times. If it’s takeaway night, offer to go get it and use the wait time to jot down ideas or sketch out new illustrations. And if downtime is the only time you have to work on your creative projects, learn to set boundaries. It’s Ok for you to occasionally request some time to work and shut everyone out.

Balance: My systems will not work for everyone and, clearly, your schedule will differ from mine, but day mapping, a list, and tools such as productivity timers/social media blockers will increase your output, just as remembering to move, eating healthily, and staying connected with friends and family will keep you mentally and physically healthy and far less stressed.

It’s all about balance. Good luck!