After it’s over—and often before it began—many a client has expressed how anxious they were about working with an editor and how little they knew about the process. Hiring an editor is a commitment of your spirit and resources, and it’s understandable that writers approach the process with caution, questions, and even some trepidation. But developmental editors are the midwives of the book world, as more than one client has put it. We edit because we love books and love working with book creators to bring great books into being. We want your book to be as good as good as it can be, and we want the process to be as beneficial for your work—and as painless for you—as it can be.

First off, what is a “developmental” editor? That is one of the many questions freelance editors get, and I’ll share some others in this post. Not all editors work the same way, of course, but as I try to answer common questions, I’ll provide a window into my own editing process, which will likely be typical for many editors.

(I’m assuming you are reading this article because you feel that working with an editor might be beneficial to your work. The question “How do I know I need an editor?” is a topic for a post all its own, followed by “How the *bleep*do I even find a decent editor?” That said, the short answer is that ALL writers need an editor at some point prior to publication. If you’re self-publishing, you should consider hiring a copyeditor at minimum to proof your manuscript before you publish. More likely, your work will benefit from developmental editing, too, and further revision(s)—after all, even successful traditionally published authors go through rounds of developmental editing with their agent and then publisher.)

So here we go. The most common questions editors receive from clients and a window into the editing process…

What should I look for in an editor?

First, it needs to be said: Not all editors are created equal, and even an otherwise great editor might not be right for your job. What to look for in an ideal editor:

A specialist in the genre you’re writing in. (Don’t hire a regular copyeditor or a specialist in erotic fiction to edit a children’s picture book, for example, because picture books require highly specialized editing.)

A proven track record of traditionally published—not just self-published—books.

Years of experience: some editors have longevity for a reason (otherwise their freelance business would have failed long ago).

Testimonials and references, or choose a fully tested and vetted editor (which all editors in our Book Editing Associates network are).

Connections/networking/industry: Does your editor belong to relevant writers’ societies, such as SCBWI? Does your editor keep an eye on the industry and who’s who, go to conferences, and are they generally invested in, for example, the kid-lit community.

Personality: Are you a good match? Is the editor personable? Kind? Patient? Do you communicate well together?

Professionalism: Is the editor prompt to respond? Are her emails professional and clear, and do they answer your questions thoroughly? Does she appear to know what she’s talking about when it comes to writing and to your project in particular.

Published: Many editors are also writers, and you will find some who are published. If they have already traveled the long, grueling path to traditional publication, it’s certain they have a great deal of experience to offer their clients.

Honest: An honest and ethical editor will be truthful about what your work needs, even if it’s not what you hope to hear. Listen to them. An honest and ethical editor will agree to work with you on a basis that is best for your work. (If your work isn’t ready for end-stage copyediting and proofreading yet, for example, an editor should say so and not waste your time and money.)

Some things to be aware of:

Sample edit: Some editors are happy to provide a free sample edit, so you can get a sense of the editor’s style and what you’ll be getting. A reasonable sample edit is between three and five pages. Don’t expect any more than five pages (12 pt. text double-spaced). (However, do not expect the same for a very short work such as a picture book. Two or three paragraphs is reasonable, and personally, I won't do a sample edit for picture books.)

Contract: If an editor does not offer you a contract, be extremely wary. I would not work with an editor who does not provide a legally binding contract or a client who won’t sign one. A contract should clearly outline the services, project start and end dates, and payment schedules. And it should include all sorts of legalese pertaining to ownership, project cancellation, copyright, etc. (I’m an editor, not an attorney. Editors, get an attorney to draft one for you or check out resources for editors here!)

Confidentiality: While there should be no need for a separate confidentiality agreement (copyright law protects your work automatically, and the editor’s contract should state that your work is protected and your property), an editor should be happy to sign one if you require it.

The Internet: And as always, a ten-minute Internet search will help protect you, confirm an editor’s credentials, and tell you what others are saying about her. There are scam editing services and weak editors out there, so do your due diligence.

What sort of contact will I have with an editor?

Most contact with your freelance editor will probably be via email, though if you want to speak to an editor, you should be able to. Some editors will charge for phone time, however, so keep this in mind as you budget for editing.

A good editor will respond swiftly to emails. (It’s my policy to answer email on the day I receive it if at all possible, or the next day if not.)

In fact, during the process, the editor may not need much contact with you at all. Sometimes—typically when I am editing picture books—I do ask the writer to write a short one-paragraph synopsis, an aid to me helping them with issues pertaining to their narrative arc. But generally, it’s relatively uncommon for me to need to clarify something as I’m editing. After all, a developmental editor approaches the manuscript also as a reader—if there’s something that leaves the reader confused or wondering, it’s a sure place for the developmental editor to insert a developmental comment.

That is the job, and it mostly precludes the need for us to contact you, apart from updating you on our progress, which I do at the halfway point for short projects and once a week for longer projects.

You are, of course, welcome to contact us. (If you’re able, it’s a good idea to put as many questions as you can into less frequent emails, rather than sending multiple, frequent emails because freelancers don’t get a wage for answering emails. I find most clients are wonderful and very respectful of my time.)

What IS a developmental editor?

Firstly, there are different levels of editing. They include:

Developmental/substantive/line editing includes:

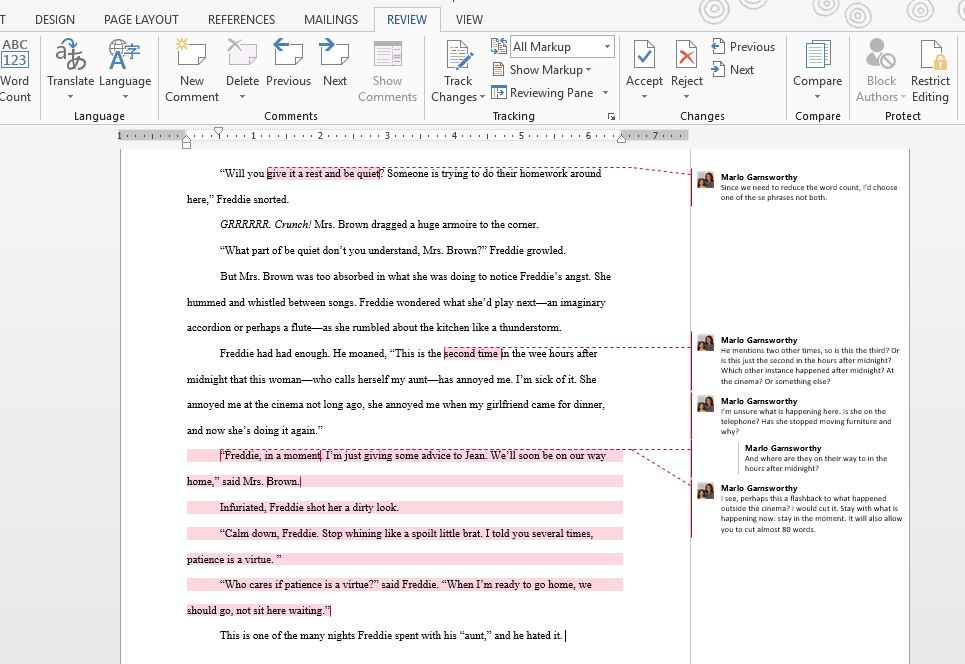

eliminating repetitive, trite, or verbose material and reducing wordiness or tightening up where needed

marking sections that need better transitional material for readability, clarity, pacing, and general “flow”

alerting the writer to missing information that is necessary for comprehension

reworking confusing or awkward writing, or suggesting ways it could be reworked

alerting the writer to technical issues, for example, POV

analyzing the big picture—the narrative arc, character development, themes, etc.

Copyediting includes:

correcting faulty spelling, grammar, syntax, and punctuation

correcting awkward language or incorrect word usage

fixing transposed words or letters

ensuring consistency in spelling, numerals, hyphenation, and capitalization

Proofreading: a final read of a developed work to catch any errors or typos.

So, developmental editing isn’t about fixing grammar, punctuation, and spelling (through some developmental editors are also copyeditors and will include that). It’s about helping you create something readable, engaging, and strong on both macro and micro levels.

Other services an editor might offer include:

- a read-through and critique or report on your work, which in my case covers areas such as:

plot/narrative structure, the big picture

character development

cohesiveness, clarity

technical aspects of writing such as POV, exposition, elision

pacing and flow

language style and dialogue

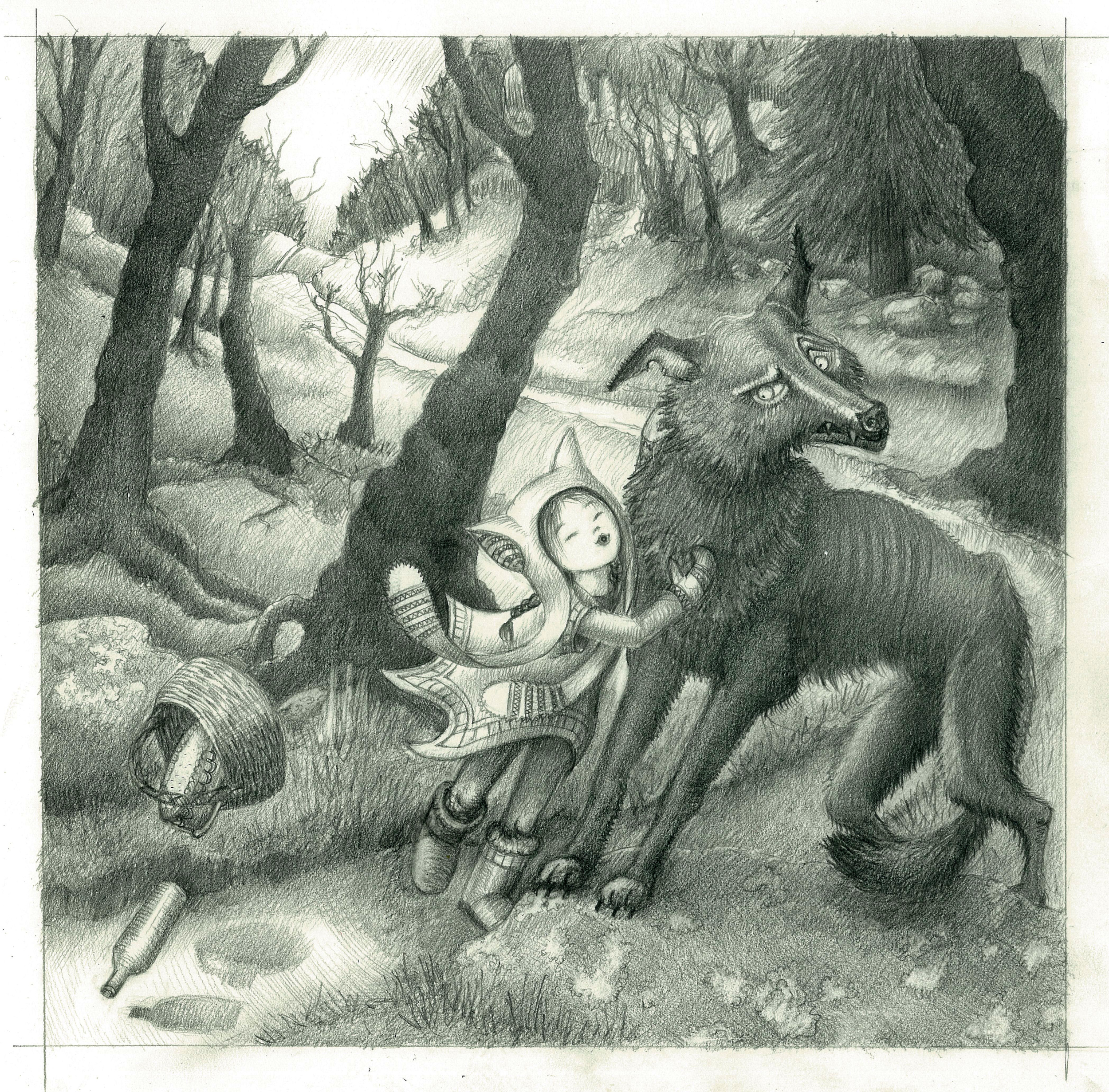

relationship between text and possible images

writing instruction specific to the genre

additional useful information and advice regarding the publishing industry

writing instruction and/or mentoring

formatting of your manuscript

editing of your query letter

ghostwriting

ongoing support and cheer-squad (not something we get paid for, but one of the nicest parts of the job)

and supplemental services such as illustration, book design, etc.

How does an editor quote?

An editor will likely ask for two things:

How long should the sample be?

For picture books, expect to send the entire manuscript. For longer works, send the first five to ten pages. If you’ve ever submitted to a literary agent or a traditional publisher, you’ll note that they have about the same submission requirements. That’s because experienced editors can determine a great deal from a short sample of the work:

Whether it will benefit from further development. Whether the writer has: a sense of narrative and character arc and how to write an engaging beginning, a voice, developed technical skills, an understanding of POV, an ability to write dialogue, etc., etc. (If there is a weakness in any of these areas, the editor will suggest developmental editing.)

Whether it mainly needs copyediting and how much: are there typos, grammatical errors, word misuse, etc. (This is really the minimum level of editing for all manuscripts, and it’s a rare manuscript that doesn’t need at least some level of developmental editing.)

The sample tells an editor what level of editing the manuscript requires and what degree of editing within that level. For example, light copyediting or heavy copy editing? Light developmental editing or heavy developmental editing?

We then use the word count and degree of editing required to perform a simple calculation to yield the fee. (Also, the number of pages in your manuscript depends on the font, font size, line spacing, margin width, and other factors, so in terms of calculating a fee, the number of pages is arbitrary. Total word count is what we need. A standard manuscript page is considered to be 250 words, so that’s what we use for the calculation: total word count ÷ 250 = number of standard pages.)

How much should editing cost?

The Editorial Freelancer’s Association rate guidelines are a great guide to what editors should and do charge.

Expect to pay a deposit. Many editors will require an initial deposit of up to 50% of the total fee. Many editors will require the balance to be paid prior to return of the project, often by the project midpoint. (This is nothing personal, but there are very few freelancers out there who haven’t been “burned” at least once in our careers by a non-paying client.)

As with most things, price is a guide to quality. Budget editing may seem like a bargain, but it rarely ends up being so. I’ve heard way too many writers say they paid for budget editing and ended up with something unpublishable due to missed errors—or worse, went ahead and published and received poor reviews about bad editing, grammar, and typos—and then paid for quality editing. Aren’t your manuscript and your budget worth quality editing the first time round?

Now you’ve chosen an editor, agreed to the level of service, signed the contract, and paid a deposit…

…What happens next?

Find out in Part 2!